“Horrification orchestrated with precision and effectiveness.”

Author | Critic

With the 2019 release of Inside the Castle, Josiah Morgan announced himself as a transgressive and exciting new voice, and Circles is further evidence. A freewheeling blur of poetry, film criticism, and visual art, Morgan’s latest work urges its readers to question what defines a text, and even what it means to read. Morgan pursues these complex problems through the attentive and varied use of typography, offering a mixture of blank-verse, concrete poetry, and essay fragments that gesture to the book’s title shape and its implications of auto-cannibalism and endlessness.

The content is as fascinating and rebellious as the form. Morgan draws on disparate media, religious references, and allusions both coded and explicit (I was particularly pleased to see one of my favorite lines from Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” and a reading of the vegan ethos in Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre). The author lays bare his frame of references in an appendix labeled ASSISTANCE [IN RESEARCH AND ERASURE], and his array of sources is fascinating and unique.

The result is not nearly as daunting or unapproachable as it might sound. In fact, I easily devoured the book in one quick sitting. Morgan’s work is energizing, animated by a vital and authentic voice, threaded with both coldly ironic observation and real despair. The author engages in some hilarious interplay between artificial designations of “high” and “low” art. Consider, for example, a prose-poem near the end of the book that describes a speaker masturbating to urolagniac fantasies of shock-punk icon GG Allin before reading Verlaine, Rimbaud, and Plath.

Much like Morgan’s excellent Inside the Castle, Circles is a powerful testament to this brilliant young writer’s talent. Keep your eyes on him.

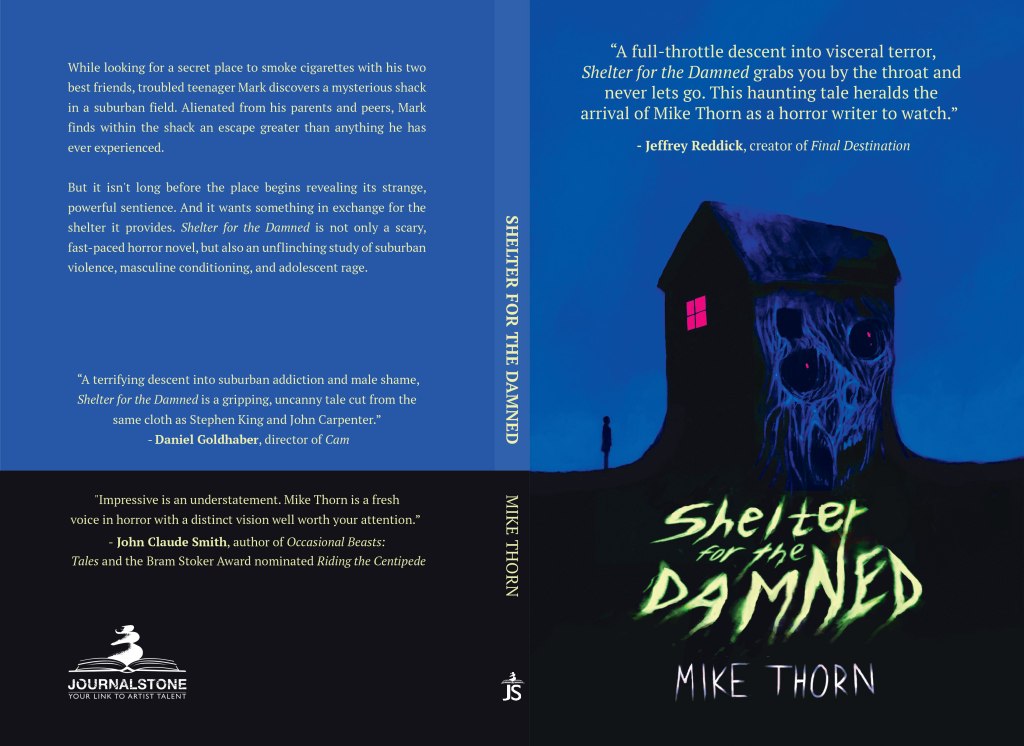

“As Mark’s friendships begin to deteriorate, so too does his school and home life, making the shack feel like the only good thing in his world. I felt that one reason Mark may have been easily swayed was his own proclivity towards violence but another may have been the implied physical abuse at the hands of his father.”

“High-octane horror that really delivers while never being too predictable. Mike Thorn respects the genre and […] is a well-read student of horror.”

Read Ray Palen’s review of Shelter for the Damned on Hellnotes.

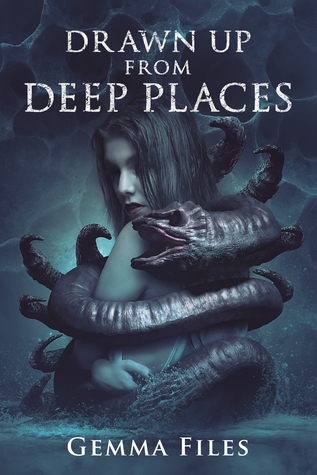

It is fascinating to assess Gemma Files’ Drawn Up from Deep Places as a collection, because the book’s construction is so uniquely connective. That is, rather than reading as an assortment of individual, isolated pieces, Drawn Up from Deep Places registers as a carefully designed, cumulative whole, comprised of two re-emerging fictional sequences woven among several standalone stories. With this text, Files displays extraordinary thoughtfulness and craft, both in conceptual and formal terms.

The collection begins with the vivid, haunting “Villa Locusta,” which situates us in an apocalyptic environment laden with mythological and religious imagery. Files further demonstrates her penchant for religious allusion with “Sown from Salt” and its companion story, “A Feast for Dust”: this duo recalls Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter, injecting a somber Western narrative with Biblical and supernatural reflections.

The bulk of the collection is devoted to another ambitious, genre-crossing series of interconnected tales. These pieces (“Trap-Weed,” “Two Captains,” the title story, and the final novelette, “The Salt Wedding”) revolve around a toxic, queer, and (sometimes dangerously) magic pirate romance aboard a ship named the Bitch of Hell.

There is also a queer horror-Western populated with demonic zombies (“Satan’s Jewel Crown”), a dark, culturally-specific love story with supernatural threads (“Hell Friend”), and an assembly of screenplay-formatted tableaus set around Jack the Ripper (“Jack-Knife,” definitely my favorite). With “Jack-Knife,” Files draws adeptly on her cinephilia and film criticism background, designing a narrative that reads both thrillingly as prose fiction and convincingly as visual text.

Drawn Up from Deep Places showcases a highly talented writer who inhabits rich genre histories and always manages to reconfigure those traditions in unusual, interesting ways. Files demonstrates stunning formal dexterity here, and a total command of voice (I am in awe of the sheer range of approaches here). This is a collection meant to be consumed as a whole, carefully designed and artfully executed. Highly recommended to adventurous readers of genre fiction.

“Shelter for the Damned is a supernatural horror story that touches on the needs of the young who have hard, sometimes abusive lives. […] I left this book with an aftertaste of unending horror and a real sense of loss.”

“[D]ark horror at its most intriguing as readers can simply read for the thrill of the darkness or interpret events in a much deeper way.”

Read the full review.

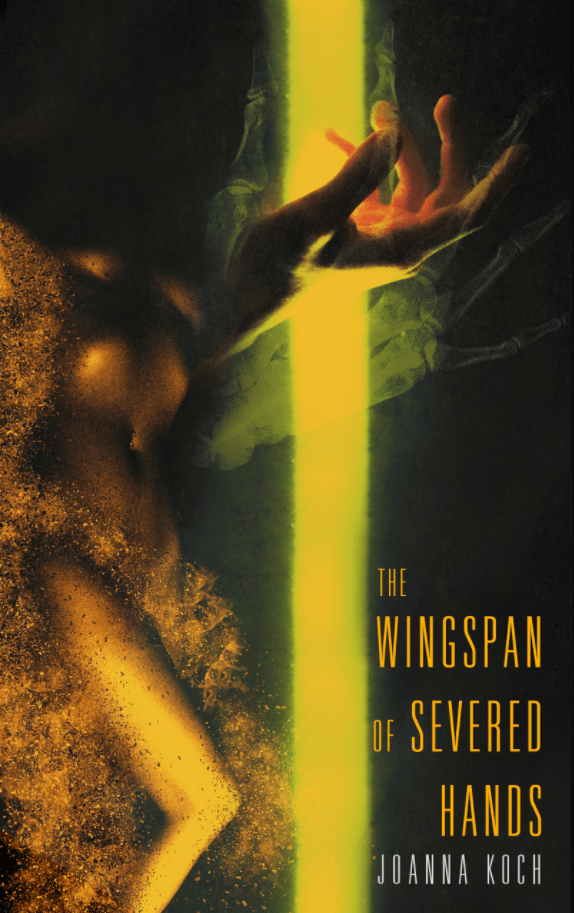

I tend to value style most highly in works of fiction. Of course, I enjoy the pleasure of sinking into a well-constructed plot as much as anyone, but for me, voice and perspective are most important of all. It is no surprise, then, that I am quite taken with Joanna Koch’s novella The Wingspan of Severed Hands, whose deliberately obstructive narrative strategies are delivered through such stunning, distinctive prose.

The story tracks Adira, a young woman who fights against misogynistic familial and social structures that aim to lay violent claim to her body. Simultaneously, it depicts Bennet, the weapons director of a secret research facility who constructs a sentient, neuro-cognitive device that develops her own disorienting self-awareness. As the novel progresses, these three characters (Adira, Bennet, and the weapon) discover a common, quasi-cosmic enemy.

This is a slippery book, whose hallucinatory sequences leak between different character POVs with stunning abandon. Koch, who has an MA in Contemplative Psychotherapy, applies Cronenberg-esque body horror to transferences of consciousness and selfhood. Much like Cronenberg, Koch intertwines institutional corruption and scientific inquiry with vivid, hyper-visceral depictions of bodily destruction and transformation. Although the novel’s climax swerves into trippy, consciousness-hopping dreamscapes, Koch seems more interested in the intimate interiority of trauma than they are in “cosmic horror” conventions.

The result is an impressive achievement, massive in scope and narrative ambition, but insular in thematic focus. Koch applies elements of experimental speculative fiction to both body and cosmic horror, placing their primary emphasis on the formidable (but ultimately beatable) power of trauma. Although the book goes to nasty places, it does not submit completely to its darkness, and I respect it for that.

Koch is a stunningly original talent, and I enthusiastically recommend this novella.